|

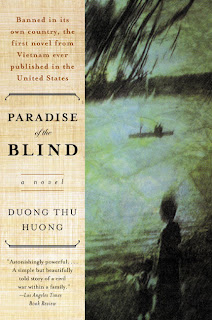

| Click here to buy this book |

As Hang makes a long

journey by train to Moscow from the small suburb where she works as an

‘exported’ textile worker, she recalls her upbringing in Vietnam, a childhood

dominated by the tragic consequences of the Communist Party’s land reforms.

First published in Vietnamese in 1998, Paradise of the Blind is the fourth

novel from Duong Thu Huong. It was a bestseller when first published, before

swiftly being banned for its criticisms of the Party, in a country where the

government retains a monopoly over the publishing industry. Duong has life

experience that will make her work identifiable to those Vietnamese who have

experienced the war and its immediate aftermath; at twenty years old she

volunteered to lead a Communist Youth Brigade sent to the front and later was

at the forefront of the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese conflict. Once a member of the

Vietnamese Communist Party, she was expelled in 1989 for her dissident views-

notably her belief in human rights and freedom of speech- and was imprisoned

for seven months without trial. Today, Duong is barred from travelling abroad

and lives and works in Hanoi. The English version of Paradise of the Blind,

translated by Phan Huy Duong and Nina McPherson, was published in 1993; it was

the first Vietnamese novel to be published in English in the USA.

Young Hang, the

protagonist of the story, remembers an upbringing as an only child, a

fatherless child, as one that was squeezed between the conflicting priorities

of those around her; from the traditional familial and spiritual values of her

late father’s long-suffering peasant sister Aunt Tam, to the communist rhetoric

of cruel Uncle Chinh, a Party cadre, and his family; with her struggling

small-capitalist mother bearing the brunt of criticism from both sides. Through

this story and other of her works, Duong serves as a courageous social

commentator. Not only does the author criticise the destruction of morality by Communist

Party policy, but demonstrates how oppressive Confucian values of the

subservience of the young to the old and of women to men, characteristic of

Vietnamese society as an influence from centuries of Chinese domination, can burden

the life a young female.

Between 1953 and 1956, Ho

Chi Minh’s Viet Minh party implemented a land reform programme in the Northern

provinces in an attempt to gain support for the anti-French resistant movement.

The chaotic forced redistribution of land to 1.5 million peasant families resulted

in families torn apart and whole communities alienated. In the case of Hang, the

result was a family torn in two; her father’s family were denounced as part of

the landlord class, despite only owning a few acres of land, and were persecuted

by Hang’s uncle on the maternal side, a ruthless Party cadre responsible for

the implementation of the programme in their village. The fragmentation of her

family haunts Hang decades after the programme was officially abandoned, and

its consequences permeate her young life.

A simply told story,

Paradise of the Blind holds considerable power to influence- perhaps the reason

why the Communist Party found it so threatening. The story does not only serve

to provide a political message, it could also be a source of nostalgia for

Vietnamese, particularly those living overseas. The beauty of Vietnam and the celebration

of Vietnamese food play considerable roles in this book. There are evocative moments in which young

Hang shelters under the covers of her bed in a dorm room in wintery Russia,

remembering the slum in which she lived with her mother in Hanoi- the leaky

roof of their home and the song of the crippled neighbour that could be heard

every day.

Despite the emphasis on

nostalgia and romance, I felt that at times it was possible to forget that the

story is based on Vietnamese themes and characters. In the translator’s note,

Nina McPherson explains that many Vietnamese expressions are difficult or

impossible to translate into English, and that for the sake of clarity some

things have been omitted. This translation is an American one, and often the

Americanisms that have been used made the setting somewhat less convincing to

me. Perhaps a little too much was lost in translation.

I found this novel to be

an interesting glimpse into the lives of an ordinary Vietnamese family

struggling with radical changes to their society. It is refreshing to read

something that gives an insight into the deep fractures that exist within

Vietnamese society as a result of the country’s tumultuous recent history, and

contradicts the official propaganda line adopted by the state. I read this book

in the run-up to Victory Day, the 30th of April, which will be a big

national celebration. In regards to this, I feel that reading Paradise of the

Blind has given me an eye-opening reminder of the power of propaganda,

censorship, illusion and of the reality of life under a communist regime, a

reality that is so difficult for an outsider to penetrate.

This novel has been

somewhat useful for my project in offering a glimpse into the hardships of an

average Vietnamese family struggling with poverty and the fracturing of society

at a time when the country was under political upheaval. Times have changed now

and how relevant this story, first published in 1988 and set between the 1950s

and 1980s, is to modern Vietnamese society is debatable, as the country

develops rapidly and poverty levels fall. Nevertheless, censorship and suppression

of free speech are very real in Vietnam today and it is worth remembering that

around eighty per cent of the population still live in rural areas, often

struggling with the same difficulties as those experienced by the characters in

this novel. Paradise of the Blind is a short story, it is quick to read and

overall I did not find it as compelling as I had hoped I would. Nonetheless, it

is a touching, tragic story that leaves an impression of the reality of life

and survival in post-war Vietnam and serves as a haunting reminder of the

horrors that have been endured by this hardy, private and long-suffering

population.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Leave a comment or ask me a question